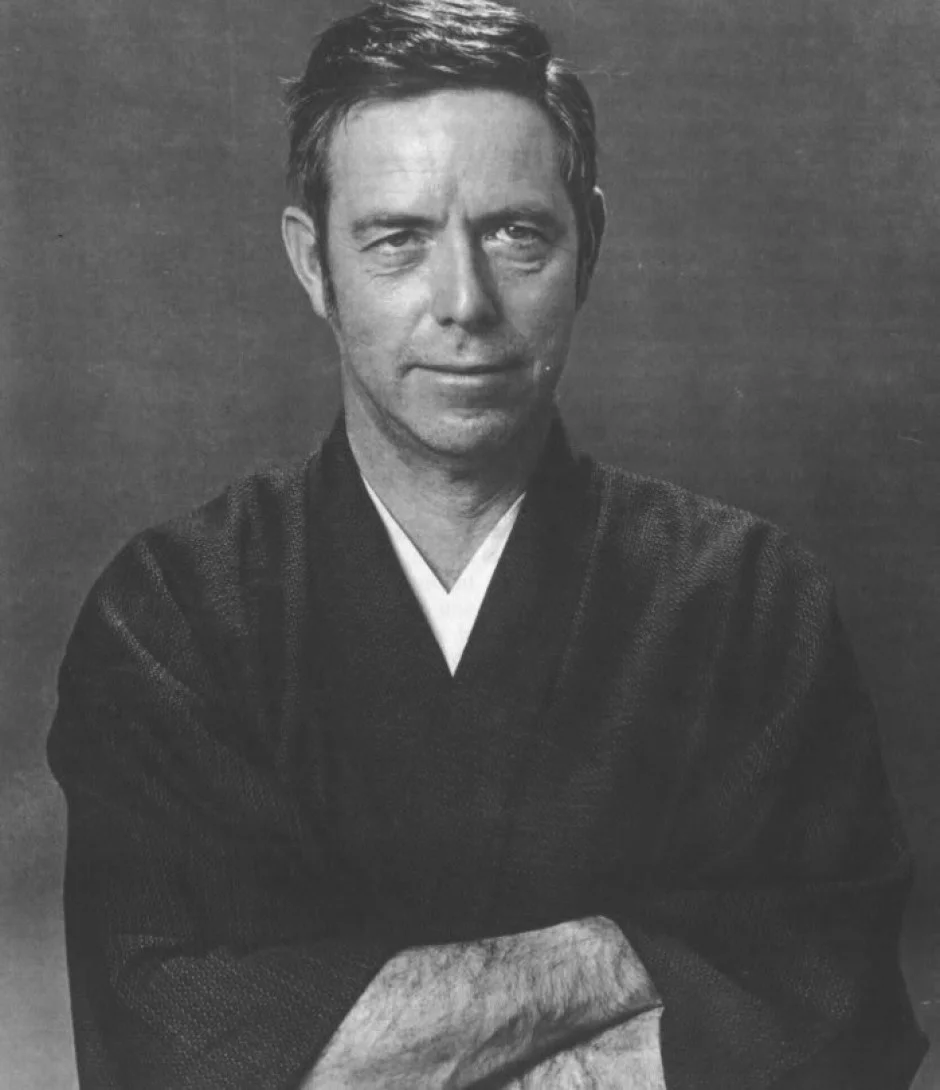

Alan Watts was a British-born philosopher, writer, and speaker. Best known for making Eastern philosophy digestible to Western minds, his radio broadcasts, books and talks turned people on to new ways of thinking. He introduced the youth culture to The Way of Zen, he put forward the idea that Buddhism could be seen as a form of psychotherapy rather than a religion, he engaged with and explored ideas of human consciousness as well as man's relationship with nature...to me at least he embodies the world-thinker, astride cultures, taking what is relevant or useful and leaving the dogma. He died in 1973 at the age of 58, at his cabin on Mount Tamalpais. Recently though, people have been setting extracts from his lectures to animations and montages, uploading them to YouTube where his words are enjoying a renaissance.

He was bright, exploring various types of meditation as a teen - he even met D.T. Suzuki - and then moved to America in 1938, just before war broke out. He became an Anglican priest, his thesis at the seminary attempting to blend contemporary Christian worship, mystical Christianity and Asian philosophy. Leaving the ministry after an affair, he went back to academics, teaching at the American Academy of Asian Studies in San Francisco, and bouncing around various other places in following years as he toured the lecture circuit, travelled in Europe, had a TV show and wrote more books.

He expanded his studies into cybernetics, Vedanta and more; experimented with psychedelics in the early 1960s; and for several years was a Fellow at Harvard. He was enjoyed by intellectuals, but had a harder time with academics. Perhaps because - as Watts said himself - he was more "philosophical entertainer" than academic philosopher.

The excellent Wikipedia entry on him, which includes tonnes of links as well as the following:

Watts did not hide his dislike for religious outlooks that he decided were dour, guilt-ridden, or militantly proselytising — no matter if they were found within Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, or Buddhism....he has been criticised by Buddhists such as Philip Kapleau and D. T. Suzuki for allegedly misinterpreting several key Zen Buddhist concepts. In particular, he drew criticism from those who believe that zazen can only be achieved by a strict and specific means of sitting, as opposed to a cultivated state of mind available at any moment in any situation. In his talks, Watts addressed the issue of defining zazen practice when he said, "A cat sits until it is tired of sitting, then gets up, stretches, and walks away." [he also said about experimenting with drugs: "if you get the message, hang up the phone".]

Though known for his Zen teachings, he was equally if not more influenced by ancient Hindu scriptures, especially Vedanta, and spoke extensively about the nature of the divine Reality Man that Man misses, how the contradiction of opposites is the method of life and the means of cosmic and human evolution, how our fundamental Ignorance is rooted in the exclusive nature of mind and ego, how to come in touch with the Field of Consciousness and Light, and other cosmic principles. His books frequently include discussions reflecting his keen interest in patterns that occur in nature and which are repeated in various ways and at a wide range of scales – including the patterns to be discerned in the history of civilizations.

And so on with the quotes...

“I have realized that the past and future are real illusions, that they exist in the present, which is what there is and all there is.”

“Playing a violin is, after all, only scraping a cat's entrails with horsehair.” “You will never get to the irreducible definition of anything because you will never be able to explain why you want to explain, and so on. The system will gobble itself up.”

“We therefore work, not for the work's sake, but for money—and money is supposed to get us what we really want in our hours of leisure and play. In the United States even poor people have lots of money compared with the wretched and skinny millions of India, Africa, and China, while our middle and upper classes (or should we say "income groups") are as prosperous as princes. Yet, by and large, they have but slight taste for pleasure. Money alone cannot buy pleasure, though it can help. For enjoyment is an art and a skill for which we have little talent or energy.”

“What we see as death, empty space, or nothingness is only the trough between the crests of this endlessly waving ocean. It is all part of the illusion that there should seem to be something to be gained in the future, and that there is an urgent necessity to go on and on until we get it. Yet just as there is no time but the present, and no one except the all-and-everything, there is never anything to be gained—though the zest of the game is to pretend that there is.”

“Your body does not eliminate poisons by knowing their names. To try to control fear or depression or boredom by calling them names is to resort to superstition of trust in curses and invocations. It is so easy to see why this does not work. Obviously, we try to know, name, and define fear in order to make it “objective,” that is, separate from “I.” “I owe my solitude to other people.”

“Like too much alcohol, self-consciousness makes us see ourselves double, and we make the double image for two selves - mental and material, controlling and controlled, reflective and spontaneous. Thus instead of suffering we suffer about suffering, and suffer about suffering about suffering.” “To put is still more plainly: the desire for security and the feeling of insecurity are the same thing. To hold your breath is to lose your breath. A society based on the quest for security is nothing but a breath-retention contest in which everyone is as taut as a drum and as purple as a beet.”

“The religious idea of God cannot do full duty for the metaphysical infinity.” “Naturally, for a person who finds his identity in something other than his full organism is less than half a man. He is cut off from complete participation in nature. Instead of being a body, he 'has' a body. Instead of living and loving he 'has' instincts for survival and copulation.”

“Jesus Christ knew he was God. So wake up and find out eventually who you really are. In our culture, of course, they’ll say you’re crazy and you’re blasphemous, and they’ll either put you in jail or in a nut house (which is pretty much the same thing). However if you wake up in India and tell your friends and relations, ‘My goodness, I’ve just discovered that I’m God,’ they’ll laugh and say, ‘Oh, congratulations, at last you found out.” “If we cling to belief in God, we cannot likewise have faith, since faith is not clinging but letting go.”

“Jesus was not the man he was as a result of making Jesus Christ his personal saviour.” “And people get all fouled up because they want the world to have meaning as if it were words... As if you had a meaning, as if you were a mere word, as if you were something that could be looked up in a dictionary. You are meaning.”

“Trying to define yourself is like trying to bite your own teeth.” [youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=khOaAHK7efc&w=700]

“Every intelligent individual wants to know what makes him tick, and yet is at once fascinated and frustrated by the fact that oneself is the most difficult of all things to know.”

“Zen is a liberation from time. For if we open our eyes and see clearly, it becomes obvious that there is no other time than this instant, and that the past and the future are abstractions without any concrete reality.” “Hospitals should be arranged in such a way as to make being sick an interesting experience. One learns a great deal sometimes from being sick. ”

“A priest once quoted to me the Roman saying that a religion is dead when the priests laugh at each other across the altar. I always laugh at the altar, be it Christian, Hindu, or Buddhist, because real religion is the transformation of anxiety into laughter.” “It is interesting that Hindus, when they speak of the creation of the universe do not call it the work of God, they call it the play of God, the Vishnu lila, lila meaning play. And they look upon the whole manifestation of all the universes as a play, as a sport, as a kind of dance — lila perhaps being somewhat related to our word lilt”

“What we have forgotten is that thoughts and words are conventions, and that it is fatal to take conventions too seriously. A convention is a social convenience, as, for example, money ... but it is absurd to take money too seriously, to confuse it with real wealth ... In somewhat the same way, thoughts, ideas and words are "coins" for real things.” “I am what happens between the maternity ward and the Crematorium”

“A successful college president once complained to me, I'm so busy that I'm going to have to get a helicopter! Well, I answered, you'll be ahead so long as you're the only president who has one. But don't get it. Everyone will expect more out of you.” “The more a thing tends to be permanent, the more it tends to be lifeless.”

“The world is filled with love-play, from animal lust to sublime compassion.” “Through our eyes, the universe is perceiving itself. Through our ears, the universe is listening to its harmonies. We are the witnesses through which the universe becomes conscious of its glory, of its magnificence.”

“Things are as they are. Looking out into the universe at night, we make no comparisons between right and wrong stars, nor between well and badly arranged constellations.” “You are a function of what the whole universe is doing in the same way that a wave is a function of what the whole ocean is doing.”

“The meaning of life is just to be alive. It is so plain and so obvious and so simple. And yet, everybody rushes around in a great panic as if it were necessary to achieve something beyond themselves.” “The art of living... is neither careless drifting on the one hand nor fearful clinging to the past on the other. It consists in being sensitive to each moment, in regarding it as utterly new and unique, in having the mind open and wholly receptive.”

“Advice? I don’t have advice. Stop aspiring and start writing. If you’re writing, you’re a writer. Write like you’re a goddamn death row inmate and the governor is out of the country and there’s no chance for a pardon. Write like you’re clinging to the edge of a cliff, white knuckles, on your last breath, and you’ve got just one last thing to say, like you’re a bird flying over us and you can see everything, and please, for God’s sake, tell us something that will save us from ourselves. Take a deep breath and tell us your deepest, darkest secret, so we can wipe our brow and know that we’re not alone. Write like you have a message from the king. Or don’t. Who knows, maybe you’re one of the lucky ones who doesn’t have to.” “For unless one is able to live fully in the present, the future is a hoax. There is no point whatever in making plans for a future which you will never be able to enjoy. When your plans mature, you will still be living for some other future beyond. You will never, never be able to sit back with full contentment and say, "Now, I've arrived!" Your entire education has deprived you of this capacity because it was preparing you for the future, instead of showing you how to be alive now.”

“We seldom realize, for example that our most private thoughts and emotions are not actually our own. For we think in terms of languages and images which we did not invent, but which were given to us by our society.” “To have faith is to trust yourself to the water. When you swim you don't grab hold of the water, because if you do you will sink and drown. Instead you relax, and float.”

“It's like you took a bottle of ink and you threw it at a wall. Smash! And all that ink spread. And in the middle, it's dense, isn't it? And as it gets out on the edge, the little droplets get finer and finer and make more complicated patterns, see? So in the same way, there was a big bang at the beginning of things and it spread. And you and I, sitting here in this room, as complicated human beings, are way, way out on the fringe of that bang. We are the complicated little patterns on the end of it. Very interesting. But so we define ourselves as being only that. If you think that you are only inside your skin, you define yourself as one very complicated little curlique, way out on the edge of that explosion. Way out in space, and way out in time. Billions of years ago, you were a big bang, but now you're a complicated human being. And then we cut ourselves off, and don't feel that we're still the big bang. But you are. Depends how you define yourself. You are actually--if this is the way things started, if there was a big bang in the beginning-- you're not something that's a result of the big bang. You're not something that is a sort of puppet on the end of the process. You are still the process. You are the big bang, the original force of the universe, coming on as whoever you are. When I meet you, I see not just what you define yourself as --Mr so-and- so, Ms so-and-so, Mrs so-and-so-- I see every one of you as the primordial energy of the universe coming on at me in this particular way. I know I'm that, too. But we've learned to define ourselves as separate from it. ”

[[ps - please check out some of my other quote collections here - The Guy Quote]]

Early in the morning on the fifth of February AD 62, a gigantic earthquake rippled beneath the Roman province of Campania and in seconds, killed thousands of unsuspecting inhabitants. Large sections of Pompeii collapsed on top of people in their beds. Attempts to rescue them were stopped when fires broke out. The survivors were left destitute in only the soot-covered clothes they stood in, their noble buildings shattered into rubble. There was horror, disbelief and anger throughout the Empire. How could the Romans, the world’s mightiest, most technologically sophisticated people, who had built aqueducts and tamed barbarian hordes, be so vulnerable to the insane tempers of nature?

Early in the morning on the fifth of February AD 62, a gigantic earthquake rippled beneath the Roman province of Campania and in seconds, killed thousands of unsuspecting inhabitants. Large sections of Pompeii collapsed on top of people in their beds. Attempts to rescue them were stopped when fires broke out. The survivors were left destitute in only the soot-covered clothes they stood in, their noble buildings shattered into rubble. There was horror, disbelief and anger throughout the Empire. How could the Romans, the world’s mightiest, most technologically sophisticated people, who had built aqueducts and tamed barbarian hordes, be so vulnerable to the insane tempers of nature? I've blogged a few nuggets by Slovenian philosopher

I've blogged a few nuggets by Slovenian philosopher  Love is one soul in two bodies.

Love is one soul in two bodies.